The role of ventilation in the carbon net zero revolution

To achieve a reduction in the UK’s carbon emissions, we need to look at BOTH the means of heating, cooling and airing a building, and our sources of supply says Roy Jones, Technical Director at Gilberts Blackpool.

Building services are under scrutiny in the commitment towards net zero: the sector accounts for almost 30% of carbon emissions in building & construction in a well-insulated building, and ventilation and cooling may account for more than 50% of the energy requirement1 The operation of buildings itself accounts for between 18% and 28% of the UK’s emissions and the built environment in total up to 25%2. The places where we work and play - including offices, factories, hospitality, and retail- represent 70+% of non-domestic energy consumption.

We must not forget embodied carbon- the GHG emissions associated with building construction, including those that arise from transporting building materials to the site, as well as the operational and end-of-life emissions associated with those materials. Buying British not only improves sustainability but helps offset the impact of rising transport costs. Even considering the materials from which the various components are made can help: aluminium, for example, can be infinitely recycled. The problem the construction industry faces currently are that it is not geared up to efficiently deal with the recycling of materials when a building reaches the end of its life- but that’s a topic beyond this!

To focus on the building services, we are lucky in the UK in that our (current) climate is ideally suited to optimise the use of energy-driven systems. With a mild maritime climate warmed by the gulf stream, we experience cool, wet winters and warm, wet summers, rarely featuring the extremes of heat or cold common in other climates. This limited variation in extremes enables us to reduce our need and dependence for cooling and ventilation on mechanical solutions. A further consideration is that, as we build tighter, we improve the thermal performance of the building: less energy to heat, but a greater requirement to cool/ventilate.

Added into the mix are changes to our Building Regulations- the best practice guidance we should endeavour to follow, which have been updated with implementation this year. Part L- conservation of fuel and power and Part F- ventilation. The driver behind updates to Part L is inevitably carbon reduction. Part F similarly reflects this, but also addresses indoor air quality (IAQ), with a baseline for offices set at an airflow of 10l/s/person or 1l/s/m2 floor area, with CO2 monitoring and reduced ducting lengths. We further need to factor in Indoor Environment Quality (IEQ) which brings noise and air movement into the mix.

These need to be considered in conjunction with the relevant CIBSE guidance- specifically AM10 and AM13- and other sector-specific documentation such as Health Technical Memorandum (HTM) 03-01 for healthcare facilities and Building Bulletin 101 for schools.

All, as a result of the carbon zero objective, are increasingly advising the use of natural ventilation, in a whole building approach, where “reasonably practical”. According to HTM 03-01, mechanical fans alone use 40% of all electricity consumed in ventilation. The preferences for ventilation strategies now are, in order of priority:

1. natural ventilation

2. mixed mode

3. mechanical ventilation

This is, after all, the oldest means of ventilation, so more than proven in practice. Simplistically, it uses naturally occurring pressure differentials in air movement, wind, and buoyancy to deliver a steady supply of fresh air for building ventilation and space cooling. Warm air rises. Nature abhors a vacuum, so draws cooler air in the replace the rising warmer air. In a building, the process delivers the best of both worlds- little/ no energy consumption with low capital costs as there is no requirement for plant and with reduced ductwork. The useable space inside is optimised as the area required for services is reduced.

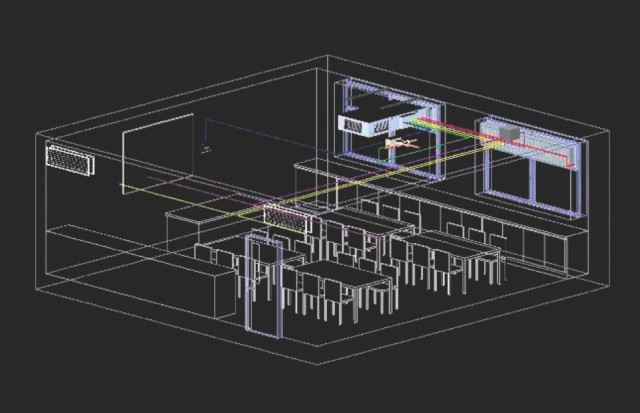

Passive natural ventilation (natvent) works best when designed into the building whilst still on the drawing board. Air paths can be effectively planned using external low-level air inlets, and internal transfer grilles to allow the fresh air through the diverse compartments, with the warm air rising up planned shafts or building structures for extraction through high-level exhausts such as roof terminals.

Especially in our ever-larger commercial buildings, and all the Building Regulations with which we have to comply in terms of fire safety, access, etc, it is- or was- difficult to retro-fit, to achieve effective air paths through the numerous storeys and compartments. Our ability to optimise natvent- or hybrid solutions- in retrofit is fundamental to the drive towards carbon zero, when you bear in mind 80% of the buildings in use by the target date of 2050 are already constructed3.

As the drive to reduce energy has risen in priority, so has technology in making natural ventilation- or versions of- a viable option in modern, multi-storey buildings. Hence the advent of hybrid or mixed mode ventilation, whereby a low energy fan supplements the air movement only when required i.e. when there is poor air movement: in effect, dynamic natvent.

Hybrid can also be a stand-alone system, with one unit ventilating one zone or compartment within the building. Therefore it is an ideal solution for successfully integrating natvent/ low carbon ventilation strategies into both new build and refit scenarios. It is further a useful tool for areas of high loading- for example where there is a high occupancy level or higher than average heat loading (from computers, printers etc). It is proven in practice: Endeavour House, a three-storey office development in Plymouth, uses hybrid ventilation and has attained a BREEAM rating of Excellent.

Latest versions of stand-alone hybrid products can be integrated with heat pumps, further optimising the low/zero carbon ambition. LPHW heat coils can be fitted, warming the internal environment and in the process eliminating the need for radiators, further reducing the energy loading and having the added advantage of optimising the floor plan.

With a little thought, it is possible to achieve the perfect balancing act, of good ventilation, good air quality and low/no energy for ventilation within an airtight building.

The trick for building services consultants going forward is to work with knowledgeable manufacturers. Working with such complexities on a daily basis, they have the in-depth knowledge to help guide you. You can then be sure that the systems you specify are as energy-efficient and environmentally friendly in all aspects as possible, helping to deliver the desired aesthetics and with the appropriate quality of internal air and comfort.

- Principle of Hybrid Ventilation, IEA Energy Conservation in Buildings & Community Systems Programme Annex 35 hybrid ventilation in new and retrofitted office buildings

- https://post.parliament.uk/research-briefings/post-pb-0044/, https://www.aiavt.org/news-events/news-details/post/embodied-carbon-in-building-materials-the-next-challenge-for-vermonts-net-zero-goals

- https://www.ukgbc.org/climate-change-2/

Roy Jones is Technical Director at Gilberts Blackpool