Are open-water heat pump systems a game changer?

Many areas of high heat demand in England have an area of open water that could serve heat-pump installations. The DECC has produced a map, and Mitsubishi Electric has practical experience of the concept — as John Kellett explains.

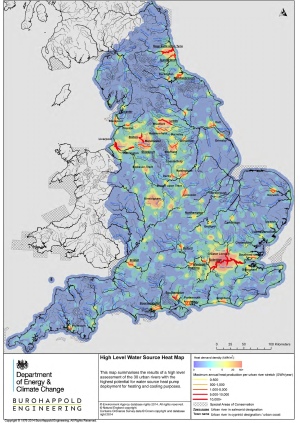

In August 2014 the Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) unveiled its open-water heat map, identifying the significant opportunities that exist for open-water heat-pump installations across the country. 40 rivers in areas of high heat demand were identified on the map, along with 10 estuary and coastal sites.

A key objective of the open-water heat map is to show local authorities, community housing associations and private developers that opportunities exist for using this renewable resource to provide a large percentage of the heat they need, and the statistics certainly back up that stance.

The bodies of water highlighted on the map each have the capacity for heat pumps to generate up to 1 MW of heat from them — enough to provide heating and hot water to around 400 to 500 homes. In the capital, The London Plan estimates the River Thames alone holds potentially 550 MW of heat, an amount which would meet 60% of all the hot-water requirements in the city.

But these figures are not just part of a futuristic grand plan, because the first UK installation which was unveiled in Kingston in 2014 has now won a multitude of awards — proving that this technology is very much a viable option. In fact, the mixed-use development at Kingston Heights, which utilises 41 Mitsubishi Electric Ecodan water-source heat pumps, draws heat from the Thames, and as a result it is estimated that 500 t a year of carbon will be saved that would otherwise have been emitted by a gas-boiler solution.

|

| This hotel at Kingston upon Thames is one of a number of buildings that is served by heat pumps drawing heat from the nearby River Thames. |

At the launch of the Kingston Heights installation, Energy secretary Ed Davey said, ‘It sounds like magic, but using proven technology we can now extract some of the heat in our rivers and estuaries and use that energy to heat our homes and offices. If we can succeed on the large scale, it would cut Britain's import bill and boost our home-grown supplies of clean, secure energy.’

The Government’s target for 4.5 million heat pumps to be in use across the UK therefore looks realistic, and it will certainly provide a strong driver for the expansion of heat pumps as a major renewable-energy tool.

An open-water heat-pump system works by recovering the solar energy stored naturally in rivers or open water. An open loop system – such as the one installed at Kingston Heights, sees water passed through filtration processes, before it is discharged back into the river. Low-grade heat is then pumped to internal plant rooms in the development where it is brought up to temperature by highly efficient heat exchangers.

This type of river-extraction system requires a licence from the Environment Agency to ensure that the water discharged back into the river is not of a temperature that will affect the ecosystems in the water. In addition, the filtration process must be sufficient to ensure that no wildlife is brought into the system.

A closed-loop system, on the other hand, utilises a network of pipes which are installed into the river. Fluid passes through this network, absorbing the heat from the river water and carrying that into the plant before repeating the cycle.

Aside from the potential for water-source heat pumps to turn vast swathes of the nation’s waterways into a giant renewable-heat source for the built environment, this use of heat pumps brings other advantages.

First they can be more efficient than their ground- and air-source counterparts because the temperature of river water is warmer than the air during the winter months as it retains some of the heat gained in the summer. The heat transfer rate from water is also higher than from the ground, which in turn gives them a higher coefficient of performance than ground-source and air-source heat pumps. So for every unit of electricity used to operate them, they can produce more hot water. Estimates in the domestic flats at Kingston Heights are that heating bills could be as much as 15% cheaper than if a gas-fired system were being used.

|

| This map summarises a number of urban rivers with the potential for water-source heat pumps for heating and cooling. |

Furthermore, extracting heat from our rivers helps offset the urban heat gain that many of the UK’s densely populated areas have experienced. As the population and development continues to increase, so too have river temperatures and the use of open-water heat-pump systems could help to reverse that trend.

A visual tool such as the open-water heat map is an incredibly powerful medium to illustrate the potential of an open-water heat-pump system. The Government is already backing heat pumps in a big way with the Renewable Heat Incentive in place for both commercial and domestic applications. In addition, the evidence from other parts of the world such as Japan and Scandinavia, where this is a proven technology, make a strong case for the UK to start exploiting this vast, untapped source of heat.

Politicians may often justifiably be accused of hyperbole, but when the minister used the term ‘game-changer’ in relation to this technology, he may just have been right.

John Kellett is general manager for product strategy with Mitsubishi Electric.